Firstly, they could "sell" their mortgages more easily, by putting them into a format which allowed economic interests in the mortgages to be transferred without the transfer of the mortgages themselves. This is "securitisation" - which means "turning into a debt security" - a debt security being banker jargon for a bond. Bonds are like bank notes: they are easily transferred: mere possession of a bond is enough to prove you own it.

Bonds are, in this way, very different from mortgages. A mortgagee lender not only has to prove the existence of the loan by means of signed, witnessed loan contracts, but also needs to register the mortgage with the land transfer authorities.

Now the ability to sell mortgage portfolios by itself wouldn't be that big a deal, as any buyer would wind up with exactly the same problem that the seller had in the first place: a buried, impossible to predict, risk of borrower default. But securitisation enables many buyers to buy small shares of the same portfolio. This permitted trick number two, which is the "special sauce".

Say you are Captain Mainwaring, and you manage a portfolio of a hundred mortgages for your bank. If you arranged these in a 10 x 10 grid, and marked the defaulted mortgages with an x, it might look a bit like this:

That is to say, defaults randomly dispersed all over the place, with no rhyme or reason to how they came about. Since you can't predict which loans will blow up, it doesn't really matter how you look at it: Captain Mainwaring has this risk. Assume that in normal economic times, about 5% of all the mortgages are likely to go bust.

But look what happens when two people share ownership of the portfolio: an ambitious investor can say: Tell you what, if you pay me three quarters of the total interest due on all the mortgages, I'll take all the defaulted loans into my share of the portfolio first. That way you'll get less interest, but you have much less risk: you'll get all your interest and principal back unless there are so many mortgage defaults that I lose my whole investment. So we can rearrange our mortgage portfolio to represent this:

Interdependent human events follow tend to follow a "power law" distribution, which has a much longer and fatter "tail" than a normal distribution. If you are interested in reading about this I heartily recommend a few books: The (MIS)Behaviour of Markets: A Fractal View of Risk, Ruin, and Reward

The other reason is related, but subtly different: The very act of creating a securitisation and changing the to the "originate and distribute" model itself changes the probabilities, because it changes the parties' interests.

Mortgages tend not to default immediately. Usually even a poor creditor will manage to make payments for six months or a year. When you originate a loan you know you'll be stuck with for 30 years, you're very careful to pick borrowers whom you think unlikely to default at any time. Having a close and personal relationship with your borrowers enables you to make these assessments with a relatively high degree of comfort - hence the relatively low level of historical defaults on mortgage portfolios. Banks of Capt. Mainwaring's persuasion used to be prudent lenders, because it was in their interest to be prudent.

Note how that dynamic changes with the originate and distribute model:

- Firstly, Banks who expect to quickly "sell down" mortgages they originate have less interest in the long term creditworthiness of the borrowers: once the securitisation is completed it is "somebody else's problem" as they no longer have risk to the borrowers at all.

- Secondly, Securitisation investors have far less ability to assess the credentials of mortgage borrowers as, unlike originating banks who lend the money, securitisation bondholders have no direct relationship with borrowers at all, and far less information about each loan. Instead they tend to rely on general due diligence done by rating agencies who are retained by originators to provide a ratings valuation for the securitisations. Rating agencies are a fit subject for another whole post.

- Thirdly, Securitisation investors have less ability to do anything should mortgages start going bad: they are reliant on third party mortgage servicing companies, who, unlike originating banks, have no "skin in the game".

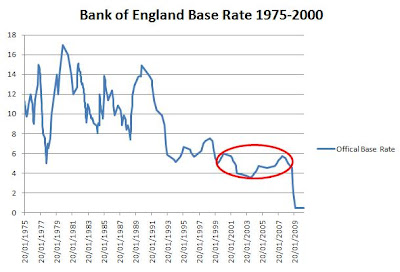

This is significant because it becomes easier to make money out of property if your cost of financing that property drops: Simply put, if you borrow £100,000 at 10% per annum to buy a property, your property has to increase in value by £10,000 in a year for you to even break even. If you borrow at 0.5%, then it only has to increase in value by £500!

These lower interest rates and a greater availability of mortgage lending meant it became viable to invest in property as a sort of investment, and before long it became almost mandatory, to avoid "falling behind":

By now, I hope, you'll see that a perfect storm was developing, and all these little developments were feeding into each other and egging each other on: Banks were now able to quickly sell their portfolios, and so were less incentivised to apply strict lending criteria. Rates were dropping, making it more compelling to invest in property. Given the returns to be had on property and the low interest rates, demand was picking up for residential property, which in turn caused property values to rise, creating more demand for mortgages, and more demand for securitised product. A classic bubble was developing.